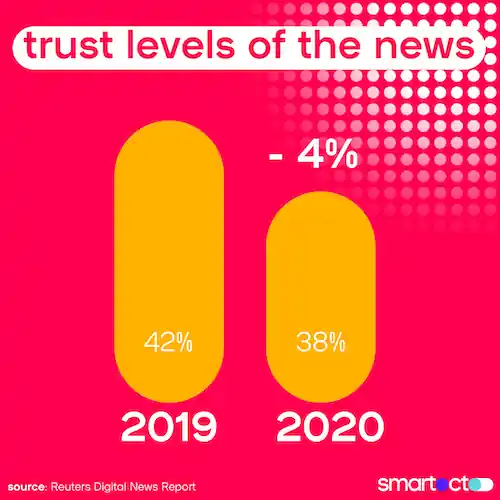

The latest Digital News Report landed recently. In it (perhaps predictably) was the sobering fact that trust levels in news media continue to slip. That report found that over the past year only 38% said they trusted the news most of the time. That’s down 4% on last year.

Trust levels in the news aren’t great. (Here’s what you can do about it)

June 30, 2020 by Em Kuntze

It’s clear that when it comes to journalism, people have trust issues. It’s not something we should ignore, but it feels that it’s something that’s often pushed to the side in the daily scramble that is the life of the newsroom. As you’re likely juggling multiple things right now, the team here at smartocto have decided to dedicate some serious time, research and brain cells to this issue over the coming months. Watch this space.

So, first off: why is trust in the news declining and should we care?

Right now we’ll say this: there are several things to blame for the decline in news, but there’s also a pretty good reason not to slump into our morning coffee.

Of course it’s important to be aware of industry-wide trends, but awareness isn’t going to help your newsroom get ahead of the issue. What it can do is jolt us into action - and the solution is right in front of us: it’s not about everyone else’s experiences. It’s about your own.

Let’s start with some depressing facts and figures

Like so many industry-ubiquitous phrases (engagement, loyalty etc), the key problem in talking about ‘trust’ is nailing the definition - and understanding how it applies to your case specifically.

Way back in 1972, Gallup polled Americans to find out the degree to which they trusted mass media. Then, 68% of respondents said they trusted it. Now, that figure - on a gently downward trajectory since the question was reintroduced in 1997 - hovers around the 40% mark (with a low of 32% in 2016).

It’s not just Gallup that paints a dim view. The freshly-published Reuters’ Digital News Report showed that public trust in journalism was down 4 percentage points from 2019. There too, less than half of respondents said they trust the news they read - and that’s a global survey.

Then there’s the issue of how Corona Virus has affected trust. In the UK, a new and ongoing research project from Cardiff University (also with YouGov & Sky) interviewed people to find out how their relationships with certain organisations has changed over the course of these months spent under lockdown. 72% of respondents said they didn’t trust newspapers. 64% said they didn’t trust TV journalists.

But, if this sounds like the final nail in the coffin of the media, that’s absolutely not the conclusion Stephen Cushion and his team draw from this research. Instead what he has found (and this study is ongoing) is that in spite of those low figures, what the project has highlighted is that people actually want more scrutiny by journalists, not less.

As anyone who works with data will tell you, the answers you get from data are only as good as the questions you input. The rigour with which Cushion and his team approached this (it really is a cracking read) reveals nuance that simple percentage points cannot. Context is key; asking questions and listening to the responses is critical.

Which leads us on to the next point: how the jiggins do you measure trust, anyway?

Ask a sample of people about whether they trust the news and surely it’s not surprising that the results are less than edifying. Even when options are given about the extent to which you trust it (implicitly, mostly, sometimes, rarely, never etc) there’s just no way these kinds of reports can convey the complex issues at hand.

As Polis’s Charlie Beckett said recently, asking if you ‘trust’ news is the wrong question:

“Do you believe, agree with, have confidence in, rely upon, use, share or interact or act upon journalism, would all be more useful questions”.

Furthermore, lumping everything into a general category of ‘journalism’ is problematic. Are you talking about the news in general? Leading national titles? Print or digital? Local? Specialised? The news you read? The news you think other people read? In your own country or from all over the world? Are well known brands more trustworthy than smaller, more local brands?

Finally, there’s the question of whether the ‘thing’ you’re trusting is the news brand, or the specific journalist from a specific news brand. Is it the trustworthiness of the (social) channels or is it the people that share content with you? It’s all in some way connected with the trust issue.

(This is an interesting read on the topic ‘who to trust’)

trust isn’t something you can measure with a browser event

It’s a human behaviour, which demands a human-centric approach to how it’s nurtured and how it’s evaluated. It’s not enough to ask ‘if’, the value is extracting the ‘why’.

The plot thickens as we weave source attribution into the mix

Over at Poynter, Taylor Blatchford says the issue is further complicated by source attribution – something which “can reduce readers’ trust by reminding them of their personal preferences and biases”. What this means is that when confronted with an article under its respective masthead, a reader’s opinion is often already partially (if not fully) formed before the first words of the article are even read.

If you’re an ardent Trump supporter, chances are you’d probably view news items emanating from The New York Times or CNN with suspicion. Our own political biases inform how and to what extent we trust specific kinds of news.

And speaking of tension between the Trump White House and The New York Times…

Fake News. It’s more than just a punchline to a bad joke, or even the 2017 word of the year: it continues to erode public confidence in news media. A recent Ipsos MORI report found that 52% of people think it’s prevalent in both print and broadcast media. Online news is perceived as being even more susceptible - there the figure rose to 62%. Oh, and those are global findings. We’re not just talking about the USA here.

If the news is framed as fake, the relationship between reader and newsroom is undoubtedly put under additional strain. It creates a situation where there’s a continuous struggle to convince, a struggle for legitimacy, a struggle to connect.

Emotion? Or cold, hard facts?

If we’re deeply entrenched in the world of journalism, we need to be self-aware enough to realise that others – our readers – quite possibly aren’t. To insert myself into this article briefly, the fact that I’m not swayed by emotive articles from The Daily Mail reveals nothing more than the fact that I just don’t process information in that way. My retired neighbour, though? Well, he’s a different story. We’ve shared many a good laugh over the years about the best place to stick our respective newspapers of choice.

Remember that comment made about President Trump by Salena Zito in The Atlantic a couple of years ago? “The press take him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally”. It’s a succinct reminder that there’s no single way that people formulate opinions about things.

This absolutely isn’t about value judgements; that’s where the profession has frequently become unstuck. Rather, it’s about individual publications understanding that if they want my trust, for example, they’re going to have to demonstrate transparency, research, and cold, hard facts. It’s about understanding what triggers your readers’ trust buttons, not your own (though chances are there is some overlap).

Trust funds journalism

There is of course another reason – if you needed it – why all this is so important.

"trust matters to news brands because a line can be drawn between trust and monetisation"

That’s Ian Gibbs writing for IJNET a couple of years ago. This is the real kicker: if you don’t trust a news brand, you’re unlikely to be prepared to pay to read it. Higher levels of trust – and loyalty as well – are likely to indicate a propensity to pay.

Trust looks different to different people and in different contexts, but what generally holds is that where levels of trust are reported as high, the publication’s content aligns with their readership’s needs.

Some achieve this by taking an ideological stance. Some by a philosophical one.

Others focus on a segment or specialised area of news content. Others on a geographical catchment.

The point is: only you know what’s going to be the magic combination for your readers. And if you don’t? Well, it’s a process, and so what if you haven’t quite figured it out yet? As Maya Angelou once said “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

Time to spring into action! What’s to be done, then?

Here’s where we become more upbeat. Well, in a moment, anyway.

Something that really stood out from that Reuters report was the fact that 46% of users don’t trust the news that they themselves use. Now, that’s the figure we should be worried about. It’s one thing to note that levels of media trust in general are on the wane, but what really matters is you. If half your readers aren’t convinced, well...

Broadly there’s a disconnect between public and media, yes, but what about your readership and your publication? Well, that’s something you have power over. If you can bolster your connection with your demographic, all the better.

Focus is everything. While it might be nice to think that everyone, everywhere trusts you, what really matters is that your readers do.

This is where we bring in the Story Life Cycle.

In talking to newsrooms, we’ve discovered that all too often too much is based on assumption rather than insight.

"Most of the world will make decisions by either guessing or using their gut. They will be either lucky or wrong."

- CEO of Mixpanel

How well do you really know your audience? Do you, for example, understand where the trust gaps lie with your subscribers? Where are they vulnerable?

the harsh truth of the new media reality is that often vulnerability comes before growth

This means asking the questions you’d probably prefer not to have to hear the answers to. Try these out for starters:

- Do you have a clear insight about why your loyal audience keeps coming back to you? (And do you know who your loyal audience are, and how they behave on your site?)

- Are you doing all you can to keep them loyal and keep them connected to topics, stories and channels that matter to them (and thus you)?

- What (real time) insights do you need to be more precise in servicing this loyal audience? (And do you have access to these insights?)

- And the million dollar question (which you can have for free): is your newsroom data-driven enough to react instantly to all the published stories that are engaging to your loyal audience?

what underpins everything is recognising that trust is a human state, not a browser event

Newsrooms who are breaking the mould and doing well understand this, and organise themselves around it accordingly. If you’re talking about raising trust levels in journalism across the board – and political divide – it’s not always about fact-checking. It’s about knowing when your audience would be most receptive to fact-checking exercises. Not all will, all the time.

After all, you can’t trust someone you don’t know. Get to know your readers - and ensure that they’re able to get to know you too.

(And it goes without saying that if you’d like some help with this, we’re only a click away. We’d love to hear from you, and we’d be happy to show you around the smartocto tool)

Want to read more from us?

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates of new blogs and other content.

You may also like...

Why the subscription model may not work for you

Subscriptions are a great alternative to ad revenue, but they may not work for everyone. Find out if that goes for you, too.

How to shift toward a paywall: a detailed guide

Adopting a reader revenue model is not as easy as installing a paywall and waiting for the subscriptions to come rolling in. Find your how-to guide here.