So the real question is: who do fact checks work for? Anyone tuning in to late night comedy in the US will be familiar with the now almost-daily monologues in which Stewart, Colbert or the entire cast of SNL unpick something or other that a political candidate has said or done. Those audiences love it. But those audiences are not, for example, Trump’s audiences. His audiences appear unmoved - even in the face of apparently reams of evidence.

A well honed - and now famous - observation in the Atlantic back in 2016 spoke to the crux of the issue: “the press take [Trump] literally but not seriously, but his supporters take him seriously not literally”. To quote another, the process of fact-checking ‘doesn’t work (the way you think it does)’.

So what should fact checking hope to accomplish?

- Hold people accountable

- Educate audiences about how to handle information

- Double down on core journalistic values of objectivity

In other words fact checking does not equal journalism. It’s a tool, but it’s only one of many that must be deployed.

What is horse race journalism?

Horse race journalism is a style of political coverage that resembles reporting on a horse race. “Politician X improves their chances of winning by advocating for Y.” The focus is on the politician's chances of gaining votes.

Here’s Jay Rosen, America’s most prominent critic of horse race journalism, explaining its appeal:

“ [Horse race coverage] is an easy way to make a complicated subject come alive for audiences. It creates excitement of a kind. Suspense. These things make it a formidable adversary.”

And how does this kind of journalism often manifest itself? Simple: polls.

A word on polls

There are several reasons newsrooms focus on polls:

- It’s considered important to describe shifts in polls because they supposedly indicate how voters are responding to statements made in the media (or during a debate). The issue is that such shifts often don’t exist, as Rick Perlstein describes well in this piece. And even when they do occur, the cause is hard to pinpoint.

- Does it influence how people vote? That’s also questionable, as voters typically choose the candidate they already favour. More fundamentally, from a democratic perspective that aligns with journalistic values, it’s better to inform people about what they are actually voting for than to report on the poll.

But many journalists and newsrooms working to maximise engagement - whether measured against article performance or community value - find issues with this approach. Focusing on the horse race puts emphasis on the horses, and there’s a limit to the public’s interest in those metaphorical horses.

What organisations like Hearken and Solutions Journalism Network and Trusting News know is this: the news people care about deeply is more likely to be the news that affects them, in their own lives, in some way.

So when Jay Rosen is asked how elections should be covered, his consistent response is that the focus should be on “not the odds, but the stakes.”

2. Solutions journalism during political campaigns

Although polls, political campaign messages, and fact-checks dominate the mainstream in journalism, there are also initiatives that take a more constructive approach. Last weekend, at the B Future Festival in Bonn, Germany, this idea was the fulcrum around which much of the discussion, debate and sessions hinged.

Constructive journalism in practice delves into grey areas and nuances, uncovers problems, and fosters debate. In one session, Manuela Kasper-Claridge, of German broadcaster Deutsche Welle, defined the aim as simply to help people grasp complex issues and identify potential paths for change.

But how can this be achieved? According to Tina Rosenberg of the Solutions Journalism Network, every editorial meeting needs someone to ask: "Is there a solutions angle possible in this story?"

So what is a good solutions approach when covering the US presidential elections?

Rosenberg’s initial response was that it’s nearly impossible. But then she offered a very targeted strategy: "Talk to your community and ask them: what are the most important topics you care about? Then ask politicians what their approach to that subject would be, and in the end, you should hold them accountable for their actions. That’s a less toxic, less horse-race oriented approach."

Many newsrooms at the festival shared examples of best practice of how to turn political topics into more digestible, inspiring stories that help readers. Canadian website The Green Line has developed what is now a highly recognisable format through which it developed a constructive angle on the housing crisis.

But sometimes it is much simpler: use the thing your audience is concerned about as the foundation for your story, rather than the story that’s clearly developed by spin doctors. Ask yourself: how can you facilitate a constructive dialogue on the issue?

The key takeaway? Measuring is knowing

This shift in approach must then be closely monitored by newsrooms. As Peter Damgaard-Kristensen, COO of the Constructive Institute, pointed out during another session: "You can't change what you don't measure."

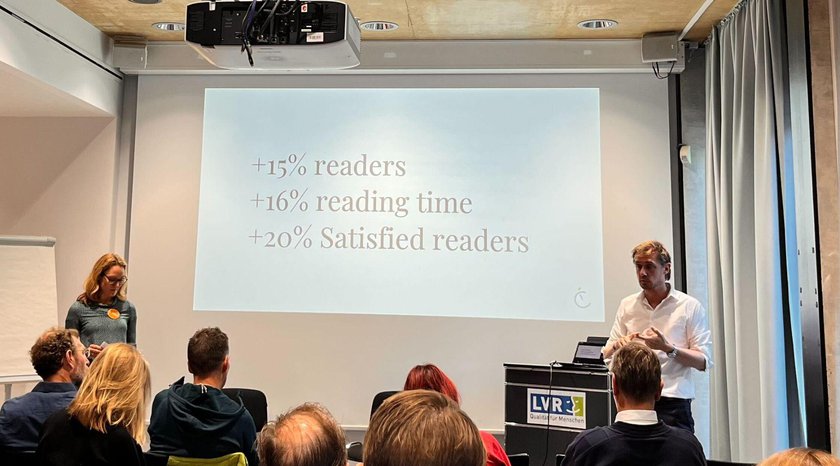

He demonstrated how a tool powered by artificial intelligence can identify and evaluate constructive articles. Furthermore, he showed that media outlets serious about adopting this approach have seen a tangible increase in engagement with their articles.